You overslept before an important meeting. You rush through the house with your heart in the pit of your throat. It’s snowy and the car is covered in a sheet of ice. You don’t know where the snow scraper is, and you forgot the computer in the apartment. Five minutes later you are back with the computer and scraping the frost off the windshield with your credit card. The phone is low on battery and disconnects before you have time to ask your work colleague to start the presentation to the customers without you. Of course there is road work, queues and there are too many red lights. Heavily late, you rush into the foyer at work, comb your hair, and step into the conference room where you pull a mugger for the customers as to why you are late. You realize you brought the wrong computer with you. The presentation is thankfully available in the cloud, but Wi-Fi is down.

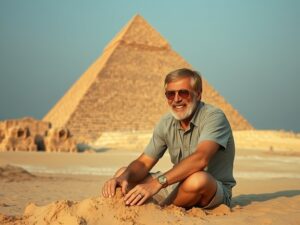

An accident rarely comes alone and it can be tempting to blame Murphy, the weather and/or God Almighty. But believe me, it doesn’t get any less steep just because you complain. What we can change is our attitude to the slope, and for me, who is Sweden’s top high-altitude climber with seven 8000 m mountains climbed and a Guinness World Record (climbed the highest mountain on every continent on the planet in record time), I know that if not my thoughts , speech and behavior bring me closer to my goal then I need to change the way I think, speak and behave because otherwise I will get the same result. Also, for me as a climber, it only gets more interesting the steeper it gets so “read my lips”, stop whining. Winners embrace the suck and love headwinds.

I remember how my climbing career once started. During my ranger service at the I22 regiment in Kiruna, we had an exercise around Kebnekaise and my combat partner Hedlund, who was a calm and composed northerner, accidentally cut his hand with his “Crocodile Dundee” knife. Blood flowed like it had been taken from a horror movie and several of us became completely us and rushed back and forth like crazy chickens with first aid kit in full swing and tried to help Hedlund who stood unmoved and watched the commotion. “It doesn’t get better because you get fired up,” Hedlund promptly exclaimed.

It is sometimes tempting to exaggerate the situation when the stress is on. However, it rarely helps unless it’s about pulling a fishing story, but during a crisis, a cool head wins and sees the facts for what they are instead of a recommendation. It’s fascinating how many people doubt that the compass needle really points north when they’ve lost their orientation and the night and the cold are creeping in. Your mind creates an alternative reality more easily under stress and exhaustion and the more you practice dealing with crisis and challenges, the more resilient you become, just like a muscle that grows after exertion.

Studies show that there are three types of people during a disaster. 50% flee the scene, and some wildly. 25% become paralyzed. The remaining 25% become pragmatic and take command. How do you know who you are? Yes, not by reading theory and singing Kumbaya, My Lord but by putting yourself through trials.

I might be the most unlikely person to start climbing. I was both terrified, afraid of heights and bullied as a child. I was terrified to go out on a balcony, after all, I didn’t know who had reinforced the concrete? I if anyone had to put me through trials to know who I was.

Thoughts of disaster were as frequent as Thanatophobia (an extreme fear of death). But living a life of fear of death was unmanageable so I took the bull by the horns and with small manageable steps towards the goal of Mount Everest. However, not everyone thought it was achievable.

When I, as a seven-year-old at school, discovered the number “8848” in the world atlas and realized that Everest was the highest in the world, my teacher curtly said, “Everest, it’s never possible!” To top it all off, I lived in Närke, where we live by the jargon, “It never works, and if it does, it’s never good…” Ironically, Närke is also one of the flattest counties in Sweden. But if you set limits on what you think you can do, you also set limits on what you can accomplish.

The strange thing is that during my 25-year climbing career so far, every time I have come home from climbs in the Himalayas and headed back to my home crag, it has miraculously become “smaller.” My respect for safety has not been disregarded, oh no, I’m a cautious general who lives by what I teach – no view is worth dying for – but with bigger challenges, my preconceived notions about how tough, difficult or difficult something is rocked. I gained more skin on my nose and my perspectives were broadened.

What problems are you unnecessarily exaggerating? What challenges would be necessary and act as good exercise for your resilience to grow? The thought may sound scary, but ask yourself what’s the worst that could happen? What do you have to lose?

I have always been afraid of heights. The solution was never to avoid heights but to learn to climb!

Sincerely

Fredrik Sträng Alpinist – Speaker – Coach