By Fredrik Sträng

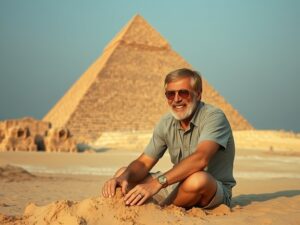

Left picture: After a K2 expedition where I lost 12 kg of weight (mainly muscle), and where I had a hard time running 5k and lifting a backpack.

Right picture: Me in the weeks before a K2 expedition, feeling like a machine, rowing 2k in 6 min 40 sec, deadlifting 200 kg, and running 10k in 38 min.

I have literally started over more than twenty times in my life. I know what it feels like to hit rock bottom. Success requires pain. Success requires dedication. Success requires consistency. However, out of the thousands of workouts I have done, I have only regretted a handful (such as working out while sick). If you want to get stronger, you must leave a part of yourself on the gym floor, and the currency is sweat, blood, and tears. If you want to climb a mountain, you need to sacrifice a part of your fitness and even take calculated risks. You cannot have your cake and eat it too. In this article, Sweden’s foremost high-altitude climber Fredrik Sträng and renowned public speaker discusses the prerequisites for success, which come at a price.

“No pain, no palm; no thorns, no throne; no gall, no glory; no cross, no crown.” – William Penn

No pain no gain

The law that dictates that if you want to move forward, you must leave something behind is the Second Law of Thermodynamics. This law states that in any energy transfer or transformation, there is always an increase in the entropy of the universe. In simpler terms, it means that in any process, some energy will be lost as unusable heat, and disorder or randomness (entropy) will tend to increase over time. Thus, to achieve progress or perform work, there must be a degradation of energy or increase in disorder elsewhere in the system or surroundings. This concept is often summarized as “you can’t win; you can only break even (at best), and you can’t break even unless you play the game.”

“No pain, no gain” – is the mantra of champions, reminding us that growth often accompanies discomfort and that you have to “waste” energy, so to speak, in order to gain something in the end.

Athletes, entrepreneurs, and I are very well acquainted with this law. Nothing great comes from nothing. Progress is built on a pile of blood, sweat, and tears.

The question I want to ask you is, if you could take a helicopter up to the top of Everest, would you do it? Here’s the thing: you cannot maneuver the helicopter; you are merely a passive passenger instructed to touch nothing and to stay in your seat and enjoy the ride. Now, ask yourself, what gives you the most pride: climbing Everest by yourself, a journey that took years of preparation and hard work, or taking the shortcut by flying to the summit?

I think that even couch potatoes would endorse that climbing Everest with your own abilities instills more gratitude and pride, even if it is significantly more arduous and painful. Even if it means that you will lose a lot of fitness and weight along the way.

The most beautiful mountain in the world

It was back in 2002. I was an aspiring mountaineer and was improving my skills in the Cordillera Blanca Mountain range. “Cordillera Blanca” is a Spanish term that translates to “White Range” in English. It refers to a mountain range located in the Andes of Peru, known for its stunning snow-capped peaks and numerous glaciated peaks, including Huascarán (6768 m), the highest mountain in Peru. I was teaming up with a French Canadian brusque middle-aged man called Verandra and a young promising alpinist, Colin Haley, to climb the awe-inspiring and brutally beautiful mountain Alpamayo (5947 m) – regarded as the most beautiful mountain in the world.

We were indeed an odd team, but we complemented each other and had a fun time. It’s interesting how the mind wanders when you have all the time in the world around the campfire on the approach or when acclimatizing to the thinner air at altitude in the higher camps. I don’t remember how it came to be, but I eventually diverted the conversation to how disconcerted I was by the fact that on expeditions, I lose a lot of weight, particularly muscles.

It’s a stated fact. On a simple expedition to the Himalayas, you can lose as much as 15 kg of bodyweight, and the majority of it is precious muscles. It boils down to metabolism. In the hypoxic thin air, the body prioritizes burning the three energy storages differently than at sea level where your oxygen saturation is close to 100%. At sea level during intense workouts, you burn carbohydrates, then fat, and in the end, muscles. At altitude, however, you are more inclined to burn carbohydrates, then muscles, and lastly fat. How come? Because burning fat requires more oxygen and oxygen is scarce at altitude.

Throughout my many expeditions to mountains around the globe, a rough estimate predicates that I have lost over 130 kg of muscles. I would have had bigger biceps than Arnold Schwarzenegger if I had refrained from climbing mountains! Not quite, but the figures are real and staggering.

I remember it so clearly when I mourned about the loss of fitness and muscles that mountaineering inflicts on us and the surprising remark that Colin made. “You are losing your kilos for something that you love,” he concluded. That is when the penny dropped. I cannot climb mountains which I love without leaving something behind. And in this context, unless I do not eat constantly to make up for the energy output/input deficiency, I will inevitably lose muscles. So, I have to ask myself, do I deem it worthy to climb these lofty peaks and sacrifice muscles, or should I refrain from the art that is one of the most satisfying pursuits that I have in my life?

I want to look good naked

In 2006, I was on Mount Everest. We were a positive lot, and everyone who had joined was in their best shape ever. I got to know “Big Mike,” as we called him, an American Olympic swimmer whose aesthetics were like they were chiseled out from marble, resembling Hercules. He spent hours every day working out at the gym to perfect himself. The result would have made Arnold Schwarzenegger proud. But something was looming in his mind. Everyone thought that he would surmount Everest like a piece of cake, but reality spoke otherwise. He was starting to lag, didn’t show up, found excuses to climb higher as time went by, and eventually, he gave in and decided to venture back home. Everest was not his game, and we all were surprised. What happened?

Big Mike’s self-image was intrinsically linked with looking good naked. Everest meant losing weight and mostly muscles. He practically felt muscles washing off his body every day. All the hard effort, the assiduous work ethic that had transformed his body into a machine was gradually evaporating. He could not stand the thought of paying the price of capitulating his well-defined body to reach the summit of Everest. As a result, it impaired his self-esteem, and that is when the dream of Everest was lost. Big Mike would probably have made it to the top if he had put the differences aside, but for him, it was simply not worth it.

Is it worth it?

Have you ever given thought to all the people who end up in fourth place, who perhaps missed standing on the award podium by a split second? Did they train less than the people who took the third place? Probably not. But sometimes sheer luck, or if you prefer, coincidence, or the form of the day dictates whether or not you make it. So, the question remains, is it worth it?

Well, one thing is for certain. If you never try, you will never know for sure. I have a rule when I set out to climb treacherous peaks: I want to be fitter than what the task at hand requires of me. Meaning, I need to have a backup. I need to have reserves in case things go wrong and not only enough power to barely make it up and down. That is living life on the edge, craving for things to go exactly as planned and leaving no room for errors or mistakes. Only a foolhardy person with no plans for the future takes those risks. And in order to have this buffer, you need to train like hell.

Startups only have a 50% five-year survival rate. But how many startups go into business thinking that they are going to fail? How many who line up at the starting line at the 100-m final think that they are going to lose? The likelihood of bad weather preventing us from reaching an 8000 m peak is noteworthy. Despite this, we are climbing with unwavering determination that we can summit the mountain. Despite this, we all fail sometimes, and in the wake of defeat, we can lose money, time, energy, and weight. That is the name of the game!

Instead of grieving about what you have lost, be proud that you gave it a shot and ask yourself, what would I have thought of myself if I had never tried? So do your air squats, push-ups, and sit-ups every goddamn day because otherwise, you’re definitely not going to make it, and be prepared to lose some weight along the way.

—————-

I train people and companies so they can become a better version of themselves. I train people and companies so that they have the power to enjoy life more and reach their desired goals. No shortcuts, no BS, but fun and result-oriented training.

If you look for quick fixes or think that training will make you so muscular that your inflated biceps will prevent you from picking your nose, think again. Those are fabrications and subterfuges.

Send me a DM if you want to get into the best shape of your life!

Good luck!

———————————————————-

About Fredrik Sträng: Fredrik, in his leadership role, has summited seven of the world’s fourteen 8,000-meter peaks, set a Guinness World Record, and lectures on leadership, communication, decision-making, and crisis management.

Kind regards,

Fredrik Sträng

Climber – Speaker – Coach