Picture: Fredrik Sträng close to the summit of Broad Peak (8047 m) in Pakistan in 2018.

By Fredrik Sträng

Research shows that if we focus on how miserable our lives will be if we don’t reach our goal, it’s a more powerful driving force than if we focus on how beautiful our lives will be if we reach our goal. In this article, Sweden’s foremost high-altitude climber, Fredrik Sträng, and renowned speaker, challenges seemingly contradictory theories about finding motivation.

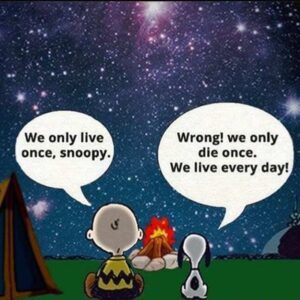

“It’s when it’s darkest that the stars shine brightest.” Harriet Beecher Stowe

An SVT reporter with a sharp tongue interviewed me about fifteen years ago, and he was clear about why I embark on seemingly life-threatening “suicide” missions, like climbing in the Himalayas. “Isn’t it so that you stand on the edge of the mountain, take a step and grab onto a cliff edge, with kilometres of air beneath your feet, thinking, that was close?” He then continued with the same brusqueness, “A bit like hitting yourself with a hammer on the head and then when you get home realize you don’t need to hit anymore and then everything is pretty nice?”

It’s no secret that life on 8000m mountains can be uncomfortable, exhausting, and risky. But this is not a lesson to convince you that Himalayan climbs are worth the effort, but this is an article that wants to challenge our common perception of finding motivation. Perhaps we have misunderstood motivation psychology? Perhaps we have missed a basic assumption that can give you express speed to reach your goals?

The SVT reporter was both right and wrong. There is no end in itself seeking near-death experiences on purpose, but I seek near-life experiences. It’s not when I get an adrenaline rush that I feel my best, but it’s in the absence of it. When I am in harmony and can control what I have control over. The rest is up to God. Where the reporter, however, hit the nail on the head was that with just the right amount of misery, you appreciate life at home even better. It never fails. After months on rock, ice, and glacier with meager freeze-dried food, constant winds whipping you, thin air challenging your claustrophobia, alternating cold and heat, with one moment where hell freezes over and another moment the panic of being trapped in a sauna, it’s like stepping into Disneyland when you get home. It’s a feast, it’s enchanting! At home, we have electricity, running clean water, a comfortable bed, food in abundance in grocery stores on every street corner, and no avalanches, rockslides, hurricane winds, or thin air trying to kill you.

The week after returning home from a major expedition in the Himalayas is like hitting the jackpot. You feel like a millionaire where suddenly everything is possible. Everything is so laid out and pampered that I walk around and smile at how easy life is here at home. Something that we easily forget after I have acclimatized to the “normal” after two months. Then the grumbling starts from the media, people you meet, and the collective mentality attaches itself like Velcro even to the most resilient. When you least expect it, you have become personality changed and must guard your thoughts, words, and actions so that you do not wallow in negativity.

How did it get like this? That I went from “ignorance is bliss” in less than two shabby months!? That’s when I end up in denial and consider myself a weak little shit. That’s when the hard training sessions, so-called “idiot sessions”, aka self-torture sessions, come in handy to free me from society’s iron grip pushing me down into the shoe soles.

I need to “punish” myself occasionally to appreciate the comfort, freedom, and peace that Sweden gives! Because it’s when a muscle is used that it becomes strong, it’s when we have little that a gift means the most, and it’s outside the comfort zone that magic happens.

It is now that my thoughts go to how we approach our dream goals in life. Research has actually shown that people tend to be more motivated when they focus on the consequences of failing to reach their goals, rather than on the potential rewards of achieving them. Thinking about the negative consequences of not reaching one’s goals can create a stronger sense of urgency and commitment to act, which can increase motivation and success in achieving the goals.

Do you feel deceived? You should. We have learned wrong since childhood. Your gut feeling may suggest that you should paint a picture of yourself standing on your “peak”, where you have succeeded, and with positive affirmations and constant reminders entice over to that side of the fence to reach your dream goal. But hand on heart, how effective has that been? You know you should exercise more, eat more salad, scroll less on social media, read more books, and listen more actively when someone talks, but how is it going?

I now invite you to a thought experiment. Imagine lying on your deathbed. You are 72 years old, way too young to die, and you feel that you haven’t at all had the chance to do the things you dreamed of, especially not the boundless ideas you had as a child. What the hell happened really? Had I reached the goal that I had set a little harder for? If I had invested a little more? Maybe you’re satisfied anyway, I mean, it could have been much worse, couldn’t it?

Now focus on something you’ve dreamed of for a long time. Maybe it’s that education, doing a Swedish classic, changing careers, volunteering, joining the Home Guard? But you keep postponing it to the future. You never get around to it. Now imagine going through your whole life without making a decision and now lying on your deathbed. You had the chance several times in life, but you never took it. Is that how you want to look back on your life? Because that’s how this motivation accumulates energy to do something about it!

So, what’s easier? Moving towards something or away from something?

The phenomenon is known as “approach-avoidance motivation” in psychology. It means that people can be motivated to approach a goal to achieve something positive or to avoid something negative. There is extensive research in the field of motivation that examines these two aspects of behaviour. Several studies have explored how different factors affect people’s motivation to approach or avoid goals. It may include individual differences, personal preferences, cultural factors, and past experiences. This type of motivation can affect behaviour, emotions, and thought patterns, and it can be crucial for how we handle different situations and strive to achieve our goals.

Avoidance motivation, also known as “negative motivation”, is about avoiding or reducing unpleasant or negative consequences. Instead of striving for rewards or positive outcomes, the individual is driven by the desire to avoid pain, failure, or other unpleasant situations. It may include avoiding risks, conflicts, or tasks perceived as difficult or frightening. In avoidance motivation, the individual may feel fear, anxiety, or apprehension about potential negative outcomes and therefore acts to avoid them.

It may also involve avoiding taking risks or not addressing challenges due to fear of failure or rejection. Avoidance motivation can be a strong driving force, but there are also risks that can lead to passivity, avoidance behaviours, or neglect of important tasks or goals. It is therefore important to balance avoidance motivation with strategies for managing fear and dealing with negative consequences constructively.

So, next time you sit down and start daydreaming about what you would like to become. Try instead of painting a picture of how athletic you will look when you cross the finish line of your dream race, visualize how untrained, lazy, and regretful you will be if you don’t take the step.

About Fredrik Sträng: Fredrik, in his leadership role, has climbed seven of the Earth’s fourteen 8,000m peaks, set a Guinness World Record, and lectures on leadership, communication, decision-making, and crisis management.

Best regards, Fredrik Sträng Alpinist – Speaker – Coach